Photo by Gustavo Torres on Unsplash

Jan 28, 2020 • Avik Das

Photo by Gustavo Torres on Unsplash

This blog post serves two purposes. First, it’s a deep-dive into a common style of interview problem, which is a topic I’m covering in my new Hiring For Tech newsletter. Secondly, the problem is a jumping off point for some more advanced topics I plan to cover in detail, including backtracking and automata.

The most basic version of this problem asks, given a string containing only ( and ), are the parentheses in the string balanced? For the parentheses to be balanced, each open parenthesis must have a corresponding close parenthesis, in the correct order. For example:

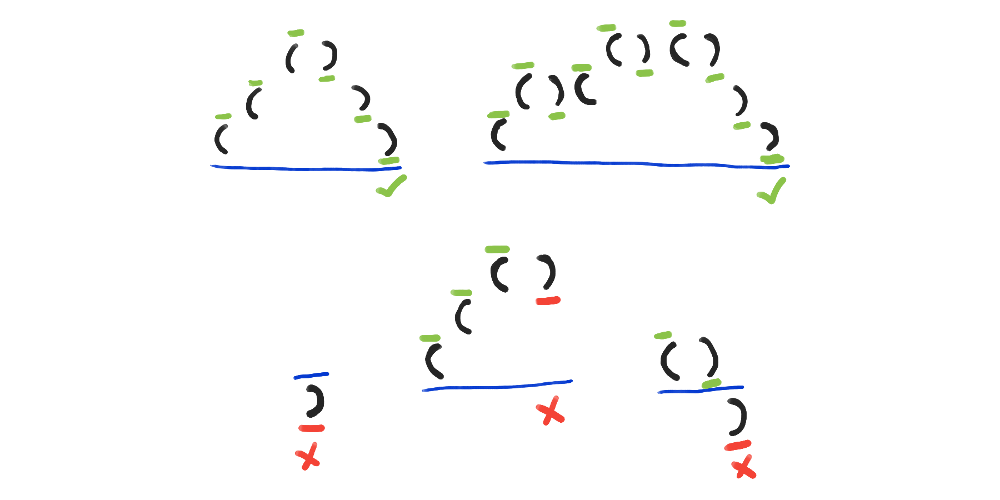

((())) is balanced.(()(()())) is balanced.)( is not balanced.((() is not balanced.())) is not balanced.One way to think about this problem is that every open parenthesis moves you away from your starting point in some direction, and every close parenthesis moves you back towards the start. You can think of the movement as getting deeper into nested rooms, or as I will do for the rest of the post, higher up a mountain.

In the “move up a mountain” approach, you need to end up back at the starting height, and you can never dip below that starting height. This is illustrated in the following diagram.

From this approach, it’s easy to see the primary piece of information we need to keep track off as we go through the input string: the current height. Each open parenthesis increases the height by one, and each close parenthesis decreases the height by one. At the end, the height needs to be zero, and we must never dip below zero.

This algorithm is easily translated into code:

def is_balanced_0(input_str):

height = 0

for c in input_str:

if c == '(':

height += 1

elif c == ')':

height -= 1

if height < 0:

return False

return height == 0

We keep around just the height, incrementing and decrementing as necessary. Furthermore, if the height drops below zero, we can terminate early.

To make the problem a little more interesting, we ask the question: what if we have other types of delimiters, like square brackets and curly braces? Like before, all the delimiters have open and close pairs, and they must match up in exactly the correct order in the input string. Again, some examples:

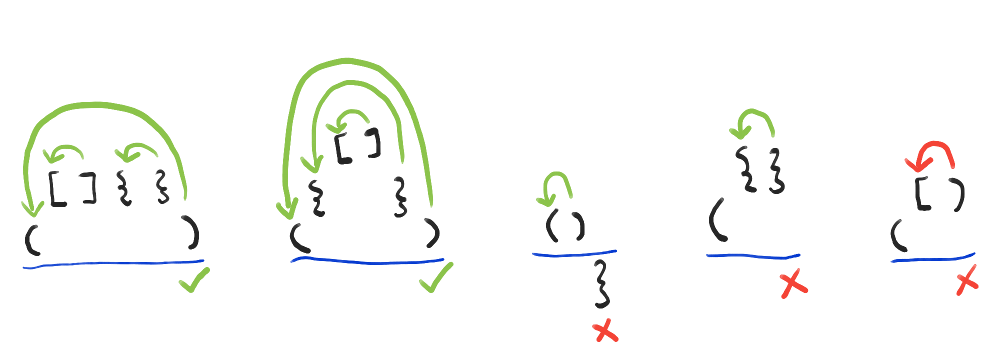

([]{}) is balanced.({[]}) is balanced.([)] is not balanced.(} is not balanced.()} is not balanced.({} is not balanced.As a starting point, we can use the same “climbing the mountain” approach as before. But this time, there’s an additional piece of information we need to track: the sequence of open delimiters that got us to our current position on the mountain. This is needed when we encounter a close delimiter, as we need to ensure the last open delimiter that hasn’t been closed matches the current close delimiter.

To represent our “path up the mountain”, we need some sort of ordered list of open delimiters that haven’t been closed yet. Additionally, we’ll only be adding to the top of the list when we encounter a new open delimiter and removing from the top when we encounter a new close delimiter. The perfect data structure: a stack.

The main modifications we need to make to our original algorithm:

Again, this is straightforward to translate into code.

def is_balanced_1(input_str):

close_for_open = { '(': ')', '[': ']', '{': '}' }

stack = []

for c in input_str:

if c in '({[':

stack.append(c)

elif c in ')}]':

if len(stack) == 0:

return False

o = stack.pop()

if close_for_open[o] != c:

return False

return len(stack) == 0

Notice again that, at the end, we need to ensure the stack has been fully emptied, meaning we’re back to the starting height.

One important property of the new algorithm is that it can be used as is even if there is only one type of delimiter. The only reason we didn’t maintain a stack before was because, when the stack only contained open parentheses, we could represent the same information using a single integer. Otherwise, the algorithms are fundamentally the same.

The last follow-up is what happens if your user can provide you with delimiter pairs? In other words, the close_for_open dictionary above is no longer a hard-coded constant, but provided by the caller.

At first glance, it seems we can use the same approach as above: maintain a stack, checking for a match every time you encounter a close delimiter. The problem is: what constitutes an open or close delimiter? Can the same character be both?

(Note: this type of insight is exactly what interviewers look for. If you can show that you understand the additional complexity introduced by a follow-up, that’s a huge plus.)

Let’s consider the following open and close delimiter pairings:

a -> A

b -> B

A -> a

The characters A and a can be either open or a close delimiters. This leads to correctly balanced strings like the following:

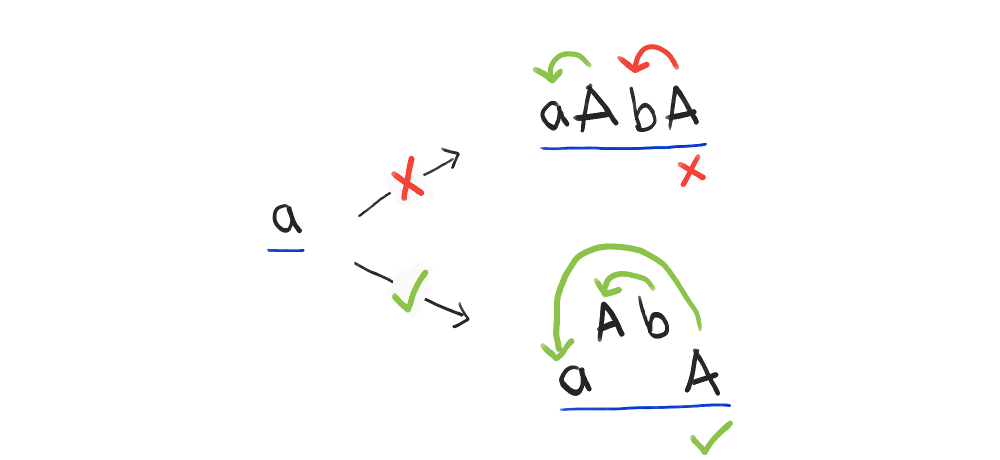

aAbB is balanced, but only if you consider a to be an open delimiter and A to be a close delimiter.AabB is balanced, but only if you consider a to be a close delimiter and A to be an open delimiter.aAaA is balanced in two different ways, either as (aA)(aA) or (a(Aa)A). Here, parentheses are used as grouping for the sake of illustration.The problem cuts deeper than these examples show, because at least in the above examples, you have enough information early on to make a decision about whether to treat a character as an open or close delimiter. Because of the symmetric mappings (a -> A and A -> a), you essentially end up being able to close pairs of delimiters as you encounter them. But consider the following mapping:

a -> A

A -> b

Then, what happens with the input string aAbA? When you encounter the first A, you have a choice: either close the first a or open a new pair of delimiters. You don’t know which one to do until you look ahead.

Because of this lack of certainty, you have no choice but to try both options. First, treat the first A as a close delimiter, then as a close delimiter. If either option (or both!) results in a balanced string, the whole string is balanced.

Trying out multiple possibilities in this way is known as backtracking, and one natural way to implement this strategy is using recursion. Now, it’s certainly possible to iterate through the input string, only using recursion when we definitely need to try two possibilities. But, it’s easier, as a first pass, to use recursion throughout.

In our new implementation, we need to define a function and some invariants on the function. Invariants are properties that will always hold, i.e. will never change. The function takes in the remaining part of the input string, the delimiter mapping and the stack so far, returning whether or not the input string can be balanced given the choices we’ve made so far. The key is the invariant, which is that the stack is exactly the same at the end of the function call as at the beginning, even if the stack is mutated in the middle.

As a convenience, we allow omitting the stack, in which case the stack is defaulted to an empty one. The base case is that no more characters are left in the input string, in which case the stack better be empty, like in our previous implementation. Otherwise, we get to work on the first character of the remaining string. Each recursive call only operates on one character.

def is_balanced_2(input_str, close_for_open, stack=None):

if not stack:

stack = []

if len(input_str) == 0:

return len(stack) == 0

c = input_str[0]

rest = input_str[1:]

The first option is that the current character is an open delimiter. This can only happen if the mapping says the character is a possible open delimiter. If that happens, we recursively attempt to balance the remainder under the assumption the current character is an open delimiter. This means pushing the current character onto the stack.

To maintain our invariant, we need to remove the current character from the stack after the recursive call. This is safe to do because, as per our invariant, the recursive call did not permanently mutate the stack.

# continuation of - def is_balanced_2

is_balanced_as_open = False

if c in close_for_open.keys(): # possible open delimiter

stack.append(c)

is_balanced_as_open = is_balanced_2(rest, close_for_open, stack)

stack.pop()

The same strategy holds if the mapping says the current character can be a close delimiter. In this case, in order to make the recursive call under the assumption the current character is a close delimiter, we have to remove the previous open delimiter from the stack. At this point, we have to make sure the stack isn’t already empty (we’re dipping below the starting height) and that the previous open delimiter matches the current character. Otherwise, the current character cannot be a close delimiter.

Again, to maintain our invariant, we have to add the character we removed from the stack back onto the stack after the recursive call.

# continuation of - def is_balanced_2

is_balanced_as_close = False

if c in close_for_open.values(): # possible close delimiter

if len(stack) > 0:

o = stack.pop()

if close_for_open[o] == c:

is_balanced_as_close = \

is_balanced_2(rest, close_for_open, stack)

stack.append(o)

Finally, we have to take the result of both branches, and see if either branch resulted in a balanced string.

# continuation of - def is_balanced_2

return is_balanced_as_open or is_balanced_as_close

Like before, this strategy of using recursion to handle each character in order could have applied to the previous two variations of the balanced delimiters problem. However, because we knew we were never going to try out multiple possibilities, it was easy to convert the recursion into iteration. When multiple choices are involved, the conversion is not so straightforward.

In this post, we looked at the balanced parentheses problem and two follow-ups to it. Each time we added a new requirement to the problem, the complexity of our implementation increased. However, later implementations, while overly complicated for the purpose, can be used to solve the earlier versions of the problem.

I have my doubts about using this type of problem in a technical interview, but from a computer science perspective, this problem has some interesting insights to offer. In later blog posts, I’ll cover these topics in more detail, so keep an eye out!