May 11, 2020 • Avik Das

Most applications can tolerate some level of errors, like a web app where the user refreshes the page if it doesn’t load the first time. But some systems require certainty, even if it takes time to achieve. A key example is a payments system, where if you tell the user their credit card is being charged, it better be charged once and exactly once.

How do large scale distributed systems achieve reliability with so many pieces? The key is an asynchronous processing system, typically built on a fundamental tool: the message queue (sometimes also known as a message “bus”).

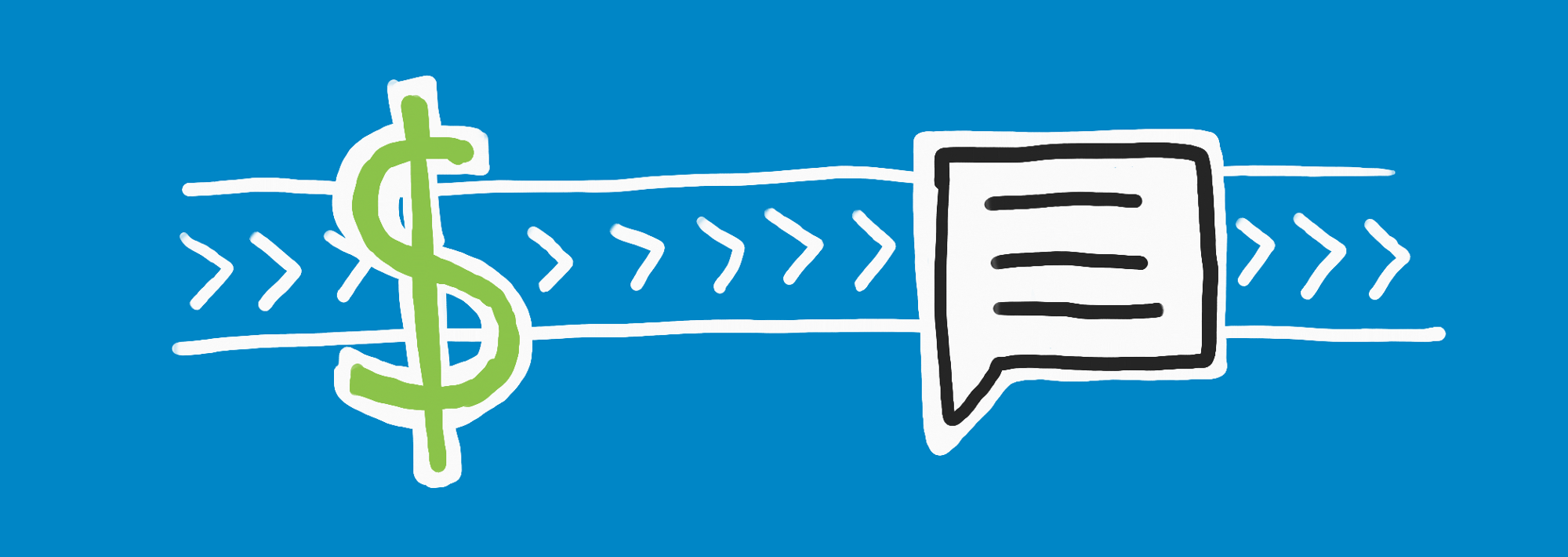

The important part of a reliable system is that once you promise to do something, you have to do it. To achieve this, it’s common to break up the processing into two parts: a synchronous part and an asynchronous part.

The synchronous part is primarily responsible for queuing up a task on the message queue, then communicating to the user the processing has started.

If the synchronous part is unable to queue the task, then it communicates an error back to the user. For example, the system may look up the user profile to determine which credit card is meant to be charged. If this lookup fails, the system reports an error. What’s important is (a) this is a recoverable error, and (b) the user has not been promised anything. They are free to try again.

Once the message is on the queue, the system has promised the payment will happen. Now, the asynchronous part of the system continually reads messages off the queue and processes them one by one. In a payments system, this means actually trying to contact the payment processor (like Visa) to make the payment.

How does a queue ensure the promise to the user is upheld? The first part of the puzzle is retrying on errors.

Suppose the connection to the payment processor is unreliable, and in attempting to make the payment, the system can’t reach the external service. Then, the system will put the message back on the queue to be processed again. This works great when the error is transient, meaning it’s expected to go away if you try again later. Connection failures fall into this category.

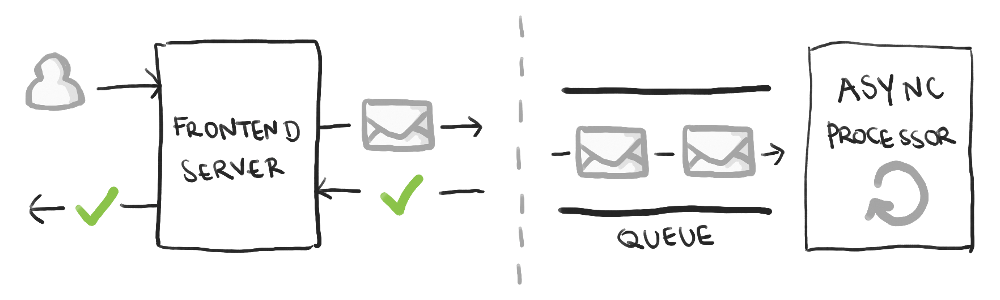

Another type of transient failure is the service crash, where a machine stops working suddenly, or an uncaught exception is encountered. To ensure the original message is never lost, it’s important the message is not removed from the queue before it is successfully processed:

If the processing succeeds, the message is removed from the queue after processing.

If the processing fails with a handled error, the original message is removed from the queue only after a copy of the message is re-queued.

If the processing crashes, the original message is simply not removed from the queue and will be processed again later.

The queue needs to be designed so a message is only sent to one processor at a time.

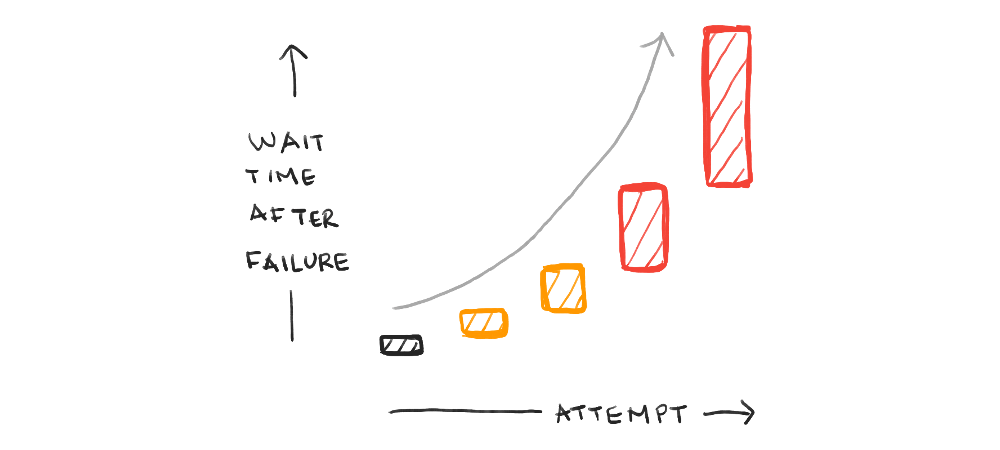

When re-queuing a message, the copied message is not processed immediately. Otherwise, transient failures like connection issues may be encountered again. Instead, the message is re-queued in a way that it will be picked up after some amount of time, which is a feature the queue needs to support.

How much time? Well, the first time a failure happens, the message should be re-processed after a short waiting period. The second time, the message should be re-processed after a longer period, and so on. Typically, the amount of time will double (or be multiplied by some other factor) each attempt, leading to what’s known as exponential backoff.

Finally, you need monitoring in place:

How often are messages being re-processed?

How many messages are taking more than one second from first being queued to being successfully processed? More than an hour? A day?

What messages are stuck on the queue the longest?

With the right processing, engineers can figure out the errors that are happening again and again, in order to fix them. The asynchronous processor can be changed and re-deployed without messages leaving the queue, so if a message has been re-queued enough times, a fix can be made to the processor before that message is processed again.

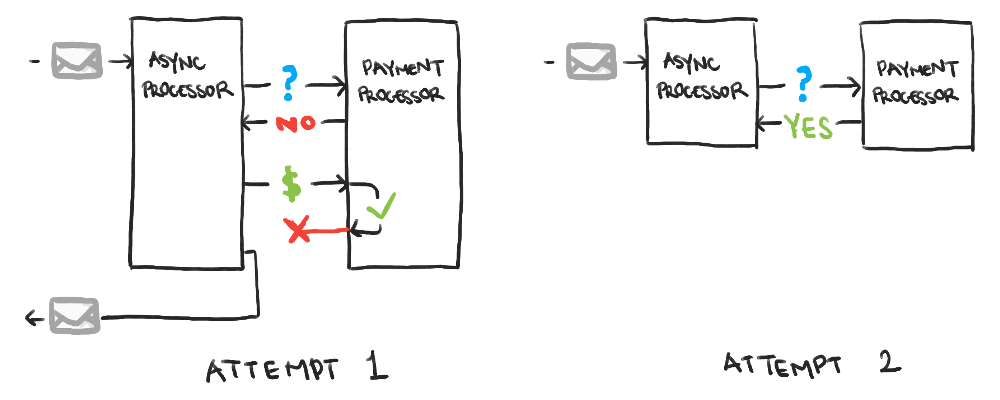

Now the system is resistant to transient failures, as well as more serious ones. But what about issues that look like failures, but aren’t? For example, the system may have contacted Visa, but the connection dropped after Visa already started processing the payment on its side. The message will be re-queued and re-processed, resulting in duplicate payments!

This is where it’s crucial the system is idempotent, meaning the same message can be processed multiple times, but the effect that message has is the same as if it were processed once.

To achieve this in a payment system, one option may be to query the external service to see if the payment went through already. By doing this as soon as a message has started being processed, no further payment needs to be initiated if it already went through earlier.

Whatever the mechanism, if there’s a possibility the message may incorrectly be processed multiple times, the requirement that the processing happen exactly once means the processing has to be idempotent.

The message queue is a versatile tool, and it’s a central piece of a reliable distributed system. By employing removal-after-processing, exponential backoff, and idempotent processing, it’s possible to bake some strict guarantees into a system architecture. Adding monitoring provides a path to handling the edge cases, further increasing reliability.

In this post, I’ve only covered how the queue is used to achieve reliability. In practice, there are many parts of the system that work together aside from just the queue, but understanding how to leverage a queue is an important starting point.