Jun 30, 2020 • Avik Das

While certain applications can tolerate some planned downtime, typical consumer-facing applications with an international audience need to be up-and-running at all hours. Clearly, with a single backend server, some downtime is inevitable. Multiple servers make it possible to avoid downtime.

Technically, even small companies will implement the techniques in this post, especially since cloud providers provide tooling for zero-downtime deployments. However, it helps to understand the underlying concepts, how easy it is to implement it yourself, and what the implications are once you reach massive scale.

Before understanding how zero-downtime deployments are possible, let’s talk about some general building blocks. These tools and techniques are useful in many contexts, not just deployments.

At a high level, graceful shutdown ensures in-flight requests are fully handled before the server shuts down.

Serving a request is not instantaneous. If your application handles many concurrent users, you may have many requests started—but not finished—the moment you tell the server to shut down.

The naive response to this shutdown request is to simply drop the in-flight requests. Not only does this lead to failed requests, but if your server processing is non-transactional, you may have completed only part of a multi-stage process, leaving your users in an incomplete state. That’s something you should always handle, but it’s still preferable to avoid these errors when possible.

Instead, a server that shuts down gracefully does the following:

While the server is running, incoming requests are accepted as normal.

Once the shutdown is initiated, new incoming requests are immediately rejected. This is necessary so the server can shut down eventually.

Once the last pre-existing request is completed, the server finally shuts down.

At this point, no new requests are accepted because there’s no running server to handle the requests.

There are other ways to avoid existing requests from being dropped (which I’ll talk about later), but the general concept of serving existing requests while not taking in new requests is a common one.

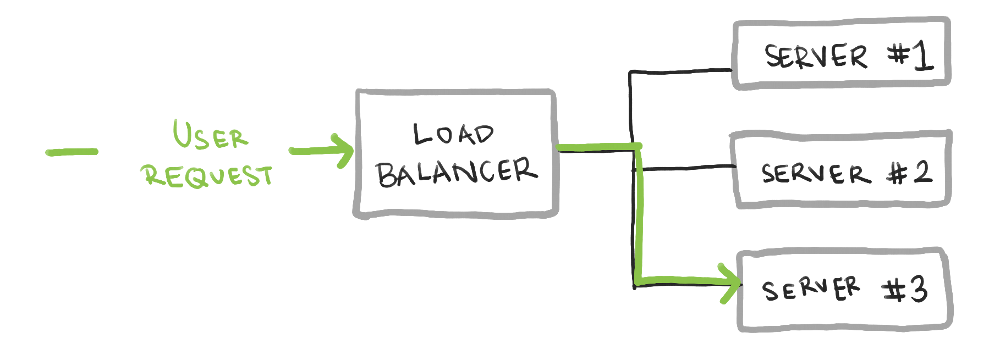

The next building block is the load balancer. A load balancer allows multiple (identical) servers to serve requests behind a single network address.

In the context of deployments, a load balancer is absolutely necessary. The multiple backing servers are what enable some server to successfully handle traffic while another server is being deployed to.

The concept of multiple servers backing a single interface is useful for many other reasons too. One is horizontal scaling: the ability to handle more traffic by adding more identical servers. Another is redundancy, not only during deployments, but also if one server faces an uncaught error that causes that server to shut down. For these reasons, you’ll see load balancers pretty much in any production environment that cares about reliability.

The last concept that’s useful to know about is dynamic request routing, especially as implemented with health checks. When a load balancer points to a fleet of servers, one or more of those servers may go offline. This can happen during the deployment, but also otherwise if a server encounters an unhandled error. In these cases, the load balancer needs to not send any traffic to those servers.

There are three ways a load balancer can stop sending traffic to a server (and once again send traffic to that server later):

Passive health checks. If the load balancer fails to reach a server during normal operation, the load balancer can mark that server as unhealthy and stop sending it traffic. While needed for unexpected server downtime, this approach means some request needs to fail, degrading the user experience. It’s also hard to know when the server is ready to accept traffic again.

Active health checks. The load balancer can make out-of-band, or non-user-initiated, requests to a separate endpoint on each server. These requests are made periodically to see if the server is healthy. In this way, the server can itself declare itself unable to take traffic, and later declare itself as ready to take traffic again.

Dynamic configuration. Some external application can tell the load balancer to stop sending traffic to a particular server, or to start sending traffic to that server. All without restarting the load balancer.

Both active health checks and dynamic configuration are ways to prepare a server for deployment, without the server failing to serve user-initiated requests.

We can now compare two strategies for zero-downtime deployments that make use of one or more of the above building blocks.

With blue/green deployments, you maintain two identical fleets of servers. Only one fleet takes traffic at a time, controlled by a load balancer. The other, unused fleet is the one you deploy to, after which you switch the load balancer to point to the newly-deployed fleet. Now, the old fleet becomes the deployment target for the next version.

Here, health checks are useful for ensuring the new fleet of servers is operational. However, health checks are not needed for the old fleet, as traffic switches to the new fleet before the old fleet actually initiates a shutdown. Mainly, dynamic configuration of the load balancer is used here.

Blue/green deployments have two huge upsides:

Deployments are fast. Servers can be deployed to in parallel, because the inactive fleet takes no traffic until the deployment is complete.

Rollbacks are painless. Because the old version of the app sticks around, a rollback is as simple as switching the load balancer to point at the old fleet of servers.

Meanwhile, the downsides are:

You need two full production environments, both of which must be identical. That means twice the number of servers, after accounting for redundancy and extra capacity.

It’s more expensive to have extremely frequent deployments, where you may even have three versions of the application running at once (the stable version, the next version that’s almost fully deployed, and the next next version that’s just getting started).

Note: if you’re willing to have the same application running twice on a single machine, you can get away with each version of the application running on a different port per machine. This would mitigate some of the overhead of parallel environments.

Rolling deployments take a less atomic approach, where an individual server is taken offline, deployed to, then brought back online. Here, “taking a server offline” means removing it from the list of available servers for the load balancer to route to. Doing so means the load balancer will not send traffic to that server for the entire duration the server is being updated.

This type of deployment does mean the fleet of servers is in a mixed state during the deployment, so the two application versions need to be compatible with each other. However, as I’ll explore in later posts, this is something you’d aim for anyway, so this isn’t that big of a downside.

Rolling deployments mean some sort of active health check or dynamic request routing is crucial. A single server has to be marked as offline before it can be shut down.

The advantages are:

Fewer resources are needed. Assuming the fleet of servers has enough redundancy to handle a few servers going down, you may not even need any extra servers to handle the deployment.

More frequent deployments are possible, as a pipeline of three versions can be prepared at peak deployment hours (the stable version, the next version, and the next next version).

The downsides are:

Deployments are much slower. Because you can’t take down all the servers at once, you have to deploy servers sequentially. This can be mitigated partially by taking down a few servers and updating them at once, but there’s a trade-off between extra capacity and deployment parallelism.

Rollbacks are painful. With the old version no longer running on extra servers, rollbacks entail essentially re-deploying the older version one server at a time.

Zero-downtime deployments ensure updates can be made available to users, without degrading their experience while the update happens. This in turn enables smaller, more frequent updates.

The cost of implementing zero-downtime deployments, however, is quite high due to the need for a load balancer and multiple servers. Fortunately, much of the added complexity is useful for other purposes, like redundancy and increased traffic handling capacity. In fact, the tools needed for zero-downtime deployments are so common that if you’re using cloud hosting, you’re probably using these tools already.

As closing note, I visualized how zero-downtime deployments can be implemented using off-the-shelf tools in my zero-downtime deployments demonstration on Github. Given how little custom code there is, I hope the demonstration makes it easy to play around with the concepts from this post.