Apr 13, 2020 • Avik Das

Once you get a certain scale, the complex systems needed to maintain that scale introduce problems that never existed before. Continuing my series on scalability concepts, I want to introduce the idea of read-after-write consistency.

Read-after-write consistency is the ability to view changes (read data) right after making those changes (write data). For example, if you have a user profile and you change your bio on the profile, you should see the updated bio if you refresh the page. There should be no delay during which the old bio shows up.

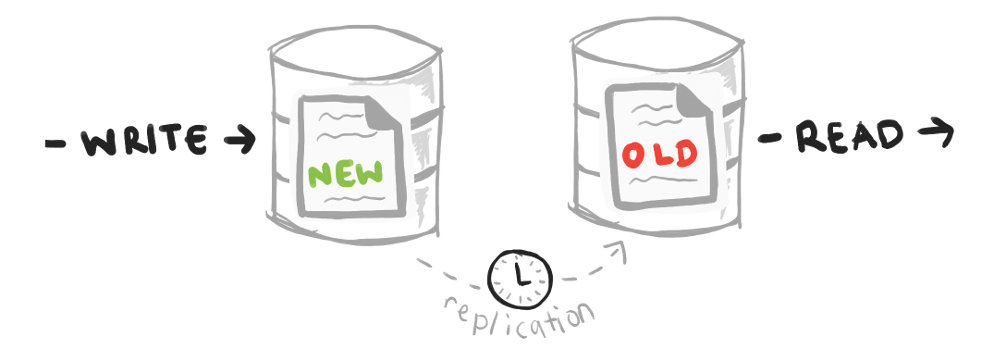

If there is a delay, this is known as a read-after-write inconsistency.

It’s important to note the consistency only applies to the one performing the write. For example, you may update your profile, but someone else may not see the update for another minute. For most large-scale systems, some amount of delay like this is inevitable, but it’s really important the original writer see their update immediately.

The root cause of read-after-write inconsistency is reading and writing in different sources. If you only have one database on one machine, you don’t have this problem, but once you scale to multiple databases, you might not be reading and writing from the same database.

This also suggests a fix for read-after-write inconsistency: ensure a single user reads from and writes to the same source at any given time.

Data partitioning is a scenario where read-after-write consistency is not violated. If your data set is too big to fit in one machine, you would partition it onto multiple machines. That means each record is stored only on one machine, so you need to figure out how to always access that record from the same machine.

(I’ll talk more about data partitioning in a later post.)

Typically, this is done by using the lookup key to figure out which machine stores that key, so you have a sort of pinning—of the sort I talk about below—already built in. The read-after-write consistency issues I discuss in this post usually involves multiple copies of the same data stored across multiple geographies.

With a general framework for how read-after-write inconsistency issues arise, let’s look at some common examples. In addition to discussing the problem, I’ll talk about the corresponding solution.

At scale, it’s often desirable to keep multiple copies of the same data. Doing so enables resilience by allowing traffic failovers in case one of the copies is inaccessible. The replicas are kept in sync.

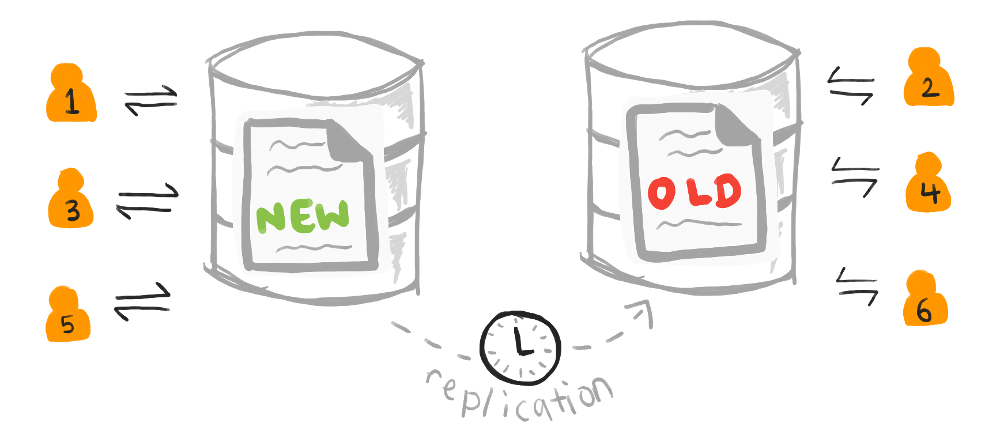

If a single user bounces between the replicas for each data access, they can write to one replica and read from another replica. To avoid read-after-write inconsistency, one of two things needs to happen.

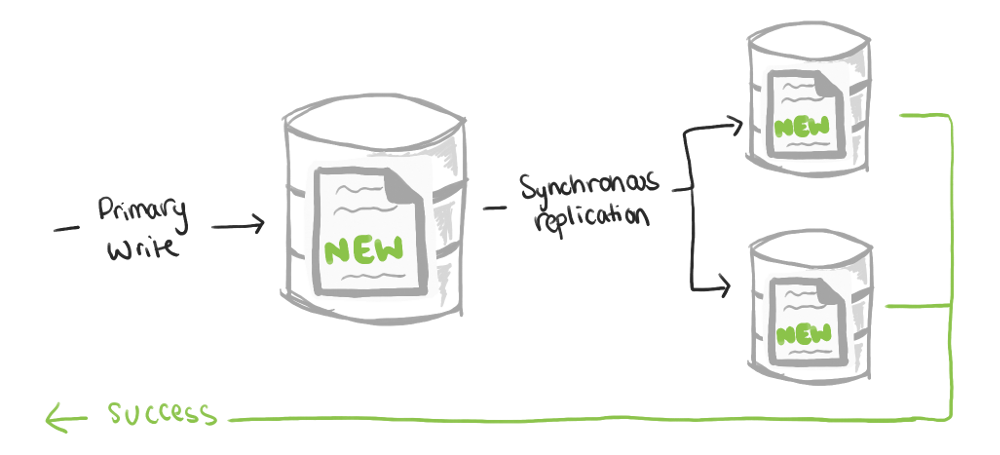

Data replication needs to happen synchronously. This means a write operation is not considered complete (and therefore success is not communicated back to the user) until the data is propagated immediately to all replicas. Unfortunately, this makes each write operation much slower, and it raises the question of what to do if one of the replications fails.

If data replication happens asynchronously (in the background), the typical solution is user pinning, also known as sticky routing. Each user is assigned a single database replica they always read and write from.

Sticky routing assignments are typically stored in a separate database, and is common when the replicas are geographically distributed. In that case, a user is assigned a replica close to them. The assignments are typically recalculated periodically to account for users moving around in the world, and whenever replications are taken offline or new ones brought online.

There’s another option, which I’ll discuss in the context of a different scenario.

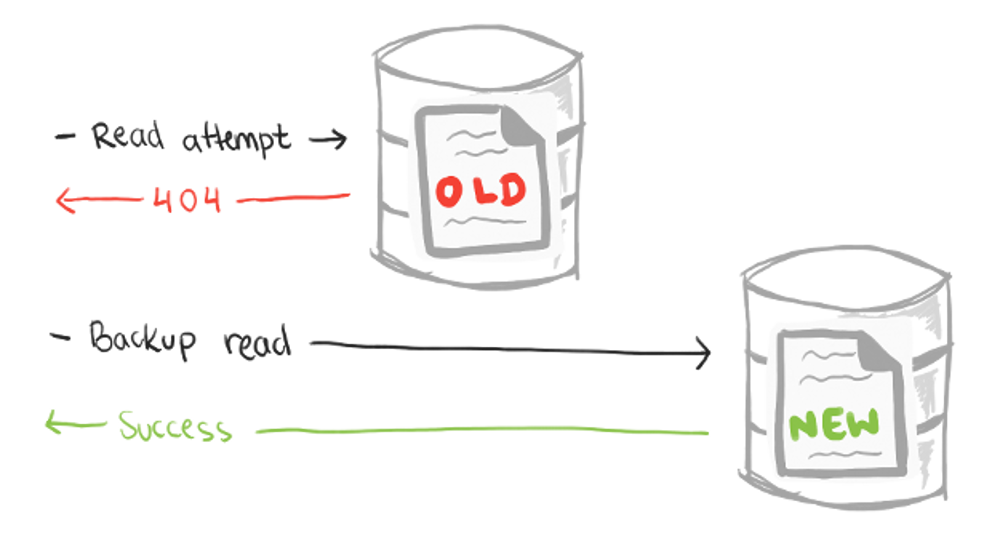

A special case of database replicas is when one database is used for writing and the remaining are used for reading. I talked about why you might want this architecture in my post about distributed ID generation, and this architecture is common when users are reading much more often than they write.

Here, sticky routing doesn’t make sense because every user writes to the same replica. Instead, lazy lookups can be employed. A read goes to any read replica, but if the requested key is not found, the application instead reads from the designated write replica. This is easier when there’s only one write replica, as you have a single place to look up data when it’s not available locally.

You have to be careful of this approach, as it makes “not found” errors very expensive in your application. If you don’t expect many such errors, then you may be okay. Furthermore, this approach doesn’t detect updated data, only new records. For example, this approach would work to find a new post, but it would not find edits to an existing post.

Note that read replicas are sometimes used for use cases like offline batch jobs, like daily data analytics. In this case, the offline job reading the data is not the same user writing the data, so read-after-write-consistency is not violated.

I said in the beginning that another viewer may not see an update immediately. For some applications, like instant messaging, we want to deliver data to other viewers instantaneously.

Unfortunately, like all problems at scale, there isn’t a perfect answer. Some of the solutions outlined above, like synchronous replication or backup reads, can help, but at the cost of speed. Ultimately, each application will have to decide which is the right approach, or even sacrifice some consistency in certain cases!

Maintaining read-after-write consistency is a consideration once your application stores multiple copies of your data. For a good user experience, it’s important the user sees any updates they make show up as soon as the application confirms the update succeeded. Otherwise, it looks like your application loses data.

When designing applications at scale, this is the type of problem I have to consider at the design stage.