Feb 19, 2019 • Avik Das

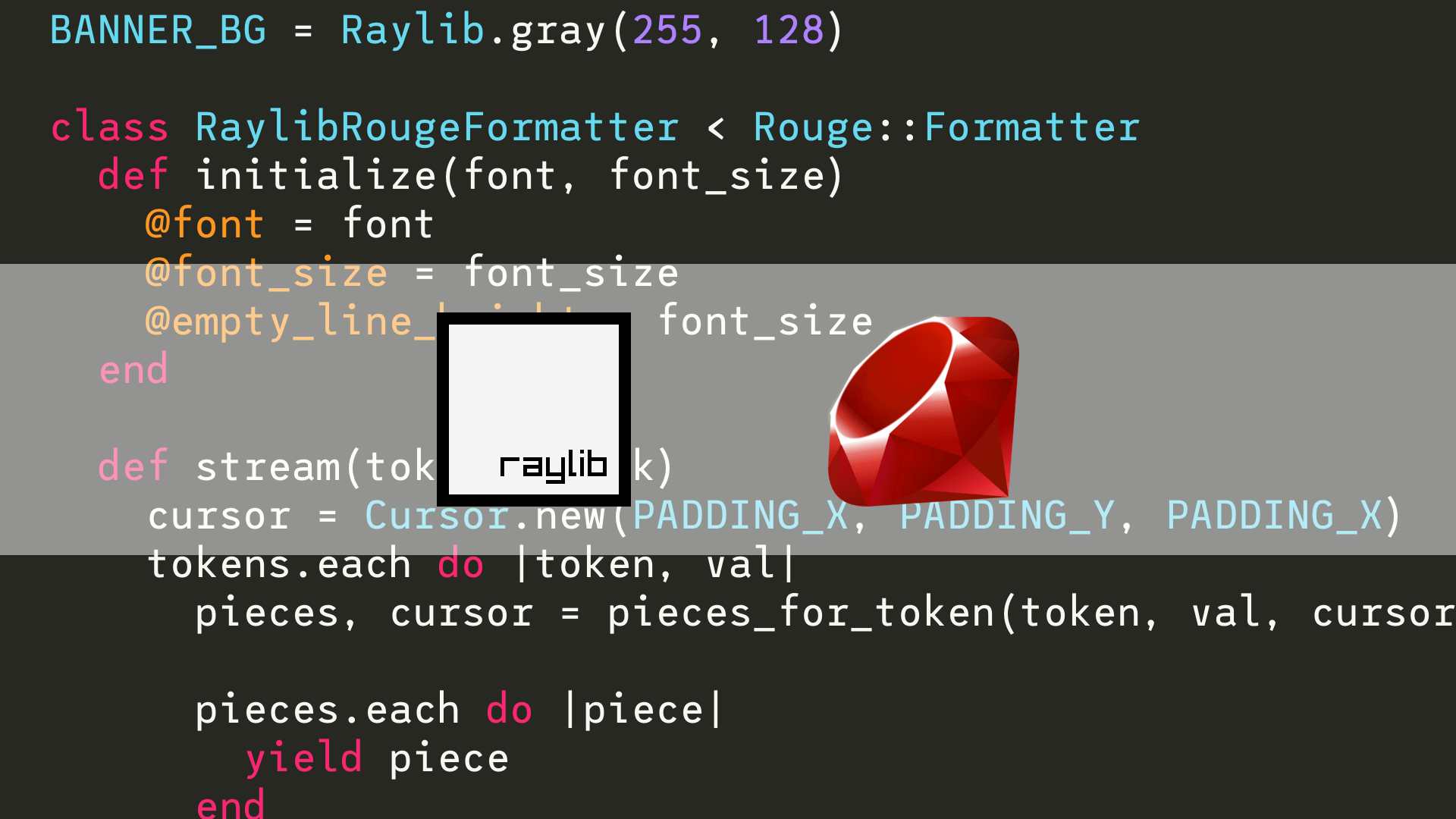

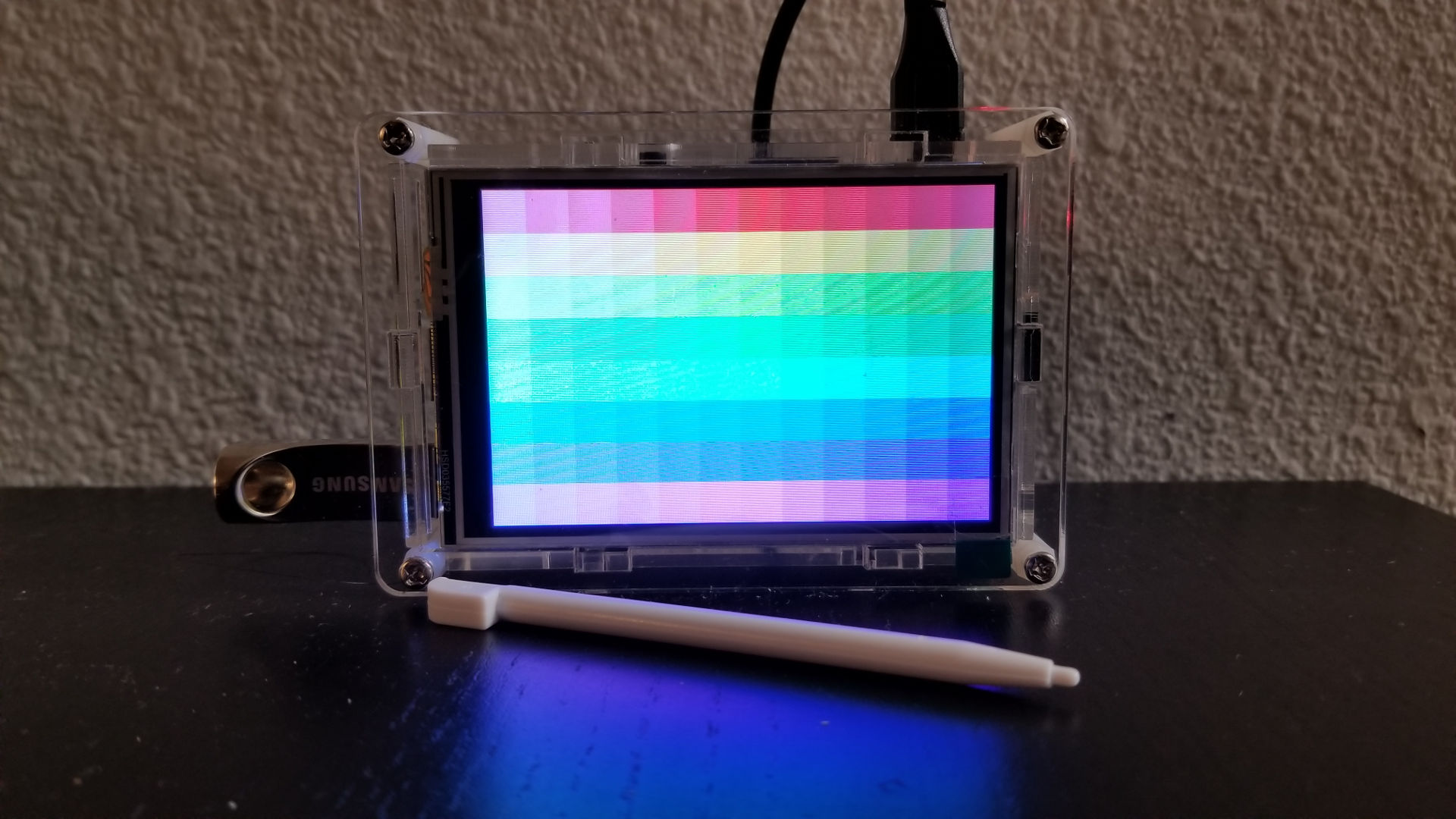

I’ve been using the excellent Raylib to create a GUI application for my Raspberry Pi. As I explained in my last post, Raylib allows rapid development of GUI applications targeting the Linux framebuffer, meaning I don’t have to run a full desktop environment for a single application.

Because Raylib is written in C, it’s easy to write applications in languages that can natively access C libraries, like C itself and C++. However, since this application is a pet project of mine, I wanted to use a higher-level language, namely Ruby. There are already bindings–ways to access the native functionality–for the library in some languages, but they suffer from some problems:

Some of them are out-of-date. For example, at the time of writing, the Lua bindings are based on Raylib 1.7 and are in the process of being ported to 2.x.

Even bindings that are more recently updated, like the Python bindings, often contain hand-written wrapper code for all the functionality in the library. This means the bindings have to be manually kept up to date with the source library.

At the time of writing, there’s no completed Ruby bindings, and I just happen to like Ruby!

In this article, I’ll walk you through automatically generating a higher-level interface to Raylib without having to write manual wrapper code that needs to be kept up-to-date. I don’t have the time to maintain a Ruby binding, but by following this guide, you can easily create a binding for your own use.

Interestingly, the Java bindings use this basic technique.

To access a C function in Ruby, we can write a native extension. Native extensions consist primarily of C functions, each of which:

To wrap around an entire library like Raylib, each function that needs to be available in Ruby needs a wrapper function, complete with type conversions. Instead of writing all these wrapper functions by hand, we can generate these bindings using SWIG, the Simplified Wrapper and Interface Generator. SWIG is a tool that automatically writes the wrapper code needed to create bindings in a number of supported high-level languages, including Ruby.

Before doing anything, let’s install SWIG. On Rasbian, you can use apt:

sudo apt install swig

(I’ve also followed these steps on my Linux laptop, so I can write the applications on my laptop before deploying them on my Raspberry Pi.)

Next, we need to tell SWIG what functions need to be wrapped. To do so, we create an interface file. Normally, in the interface file, we would declare each Raylib function. While this relieves us of the need to write all the type conversions, we still need one declaration for each function being wrapped. Luckily, if the library’s header file is not too complicated, we can actually have SWIG pull the declarations straight from the header file! That’s the approach we’ll take with Raylib.

We’ll keep extension-related files in a directory called ext/raylib. Inside, create a file called raylib.i, with the following content. As usual, I like to include many comments to remind me what each part of the file does.

/**

* The SWIG interface file for Raylib. This interface file is meant to be as

* light as possible, in order to ensure minimal work is required to keep the

* generated wrapper up-to-date with the source library.

*/

// Defines the name of the generated wrapper. For example, in Ruby, this

// results in a module named `Raylib` that will house the Ruby wrapper methods.

%module raylib

// Header section, to be inserted into the generated wrapper file. The main

// directive is to make the Raylib header available to the wrapper code, so

// that Raylib functions and data types can be referenced by the wrapper.

%{

#include <raylib.h>

%}

// Declarations, which specify which functions and data types will be made

// available by the wrapper to the high-level language.

//

// Automatically use the Raylib header to generate these declarations, which

// allows the wrapper to always be up-to-date. The caveat is that SWIG uses its

// own parser to extract declarations from the header, so care must be taken to

// ensure all the declarations in the header are correctly picked up.

%include "raylib.h"

With this header file, we can now run SWIG to automatically generate the C code that defines our native Ruby extension. When running SWIG, we need to specify the -ruby flag to build a Ruby extension. Also, if raylib.h is not available in one of the default search locations (like /usr/include), you’ll also have to specify the path to the header using the -I option.

There are some caveats though. If you try to run SWIG, you’ll get an error:

$ swig -I/path/to/raylib -ruby raylib.i

/path/to/raylib/raylib.h:151: Error: Syntax error in input(1).

The issue is the following piece of code.

// Boolean type

#if defined(__STDC__) && __STDC_VERSION__ >= 199901L

#include <stdbool.h>

#elif !defined(__cplusplus) && !defined(bool)

typedef enum { false, true } bool;

#endif

The problem is how the bool data type is defined:

stdbool.h header is available.bool type.bool is not defined, Raylib simply defines it as an enum.SWIG doesn’t use GCC or clang to parse the file. Instead, the tool implements its own parser. This parser recognizes the bool data type, but doesn’t provide any of the related defines. Raylib then tries to define an enum with the same name as the parser-recognized keyword, which SWIG considers an error.

So, what if we make sure bool is already defined, using -Dbool? No dice, because the parsing succeeds, but then we encounter another error down the line, when SWIG tries to reconcile the bool type with Ruby’s boolean representation:

$ swig -I/path/to/raylib -ruby -Dbool raylib.i

/usr/share/swig3.0/ruby/rubyprimtypes.swg:33: Error: Syntax error in input(1).

It turns out SWIG’s C parser can handle bool as though C99 were in use. We just need to provide the __STDC__ and __STDC_VERSION__ defines to make sure the correct code is executed:

swig \

-I/path/to/raylib \

-ruby \

-D__STDC__ \

-D__STDC_VERSION__=199901 \

raylib.i

And finally, our wrapper, raylib_wrap.c is created. You don’t have to worry about what’s in the wrapper code, but if you’re interested, you can open up the file. You’ll see the different types of conversions performed:

/*

* Highly simplified version of the actual generated code, annotated with

* comments.

*/

SWIGINTERN VALUE

_wrap_ClearBackground(int argc, VALUE *argv, VALUE self) {

// Check number of arguments

if ((argc < 1) || (argc > 1)) {

rb_raise(rb_eArgError, "wrong # of arguments(%d for 1)",argc); SWIG_fail;

}

// Type conversions

void *argp1;

int res1 = SWIG_ConvertPtr(argv[0], &argp1, SWIGTYPE_p_Color, 0 );

Color arg1 = *((Color *)(argp1));

// Actual function call

ClearBackground(arg1);

return Qnil;

}

The wrapper code also contains the definition of the Raylib Ruby module, and the methods under that module:

/*

* Selected code from the generated init function.

*/

SWIGEXPORT void Init_raylib(void) {

SWIG_InitRuntime();

mRaylib = rb_define_module("Raylib");

rb_define_module_function(mRaylib, "ClearBackground", _wrap_ClearBackground, -1);

}

Now that we have a Ruby extension defined, we have to compile that extension into a shared library that can be consumed by some calling Ruby code. This is where we’ll link against the Raylib library itself.

First, build Raylib as shared library. The default is a static library (.a file on Linux, for example), and Ruby extensions wrap around shared libraries (a .so on Linux, for example). The basic process of building Raylib is outlined in my last post, but now we also need the additional RAYLIB_LIBTYPE definition:

cd /path/to/raylib

cd src

# For the Raspberry Pi

make RAYLIB_LIBTYPE=SHARED PLATFORM=PLATFORM_RPI

# For desktop Linux

make RAYLIB_LIBTYPE=SHARED

With Raylib available on our system, we also need the Ruby development files, which we will consume when building the extension. If you’re using the globally-installed version of Ruby on your system, you’ll need to install the corresponding -dev package:

# For example, if you previously installed Ruby on Rasbian:

sudo apt install ruby2.3

# You'll now install:

sudo apt install ruby2.3-dev

However, because the latest version of Ruby available on my OS may be older than I like, I greatly prefer using a combination of rbenv and ruby-build to install the exact version of Ruby I want. I won’t go into how to use these tools, but know that installing Ruby this way automatically installs the required development files.

Finally, we need to create a Makefile that can compile and link our newly-generated extension code with Raylib and the Ruby C API. To do this, we use the mkmf library, included along with the Ruby development files, to generate a Makefile that can compile our extension. This is standard practice when creating a Ruby native extension.

Create a file named ext/raylib/extconf.rb with the following content. I’ll go over the different parts below, though I have included the same information as comments in my own extconf.rb.

require 'mkmf'

dir_config('raylib')

raise 'dl is missing' unless find_library('dl')

raise 'bcm_host is missing' \

unless find_library('dl', nil, '/opt/vc/lib')

raise 'math is missing' unless find_library('m')

raise 'rt is missing' unless find_library('rt')

raise 'pthread is missing' unless find_library('pthread')

raise 'brcmGLESv2 is missing' \

unless find_library('brcmGLESv2', nil, '/opt/vc/lib')

raise 'brcmEGL is missing' \

unless find_library('brcmEGL', nil, '/opt/vc/lib')

raise 'raylib is missing' unless find_library('raylib')

create_makefile('raylib')

First, we need to import the mkmf library, short for “make Makefile”.

Next, we allow the user to specify where Raylib is. As we’ll see later, we can tell mkmf to search for libraries in hard-coded locations, but dir_config allows the user to configure these locations when running the script, specifically for one library. I’ll show an example of specifying these locations down below.

Next, we go through the libraries we need to link with Raylib one by one, asking mkmf to include that library as part of the linking process. If you look in the generated Makefile, you’ll find these libraries present as -l flags to the compiler. A few notes on these libraries:

The libraries we’re searching for are Raylib itself, and all the same libraries we would have linked with if we were building our application in C. Again, the list of required libraries, including where you would find them, is covered in my last post. In particular, this means when I built the extension on my Linux laptop, I had to specify a different set of libraries to link to.

The find_library function takes the name of a library to link, a second parameter that we’ll ignore, and a series of locations where to find that library. For standard libraries, like m (for “math”), we don’t need to specify where to find the library because the compiler will already look in the right place to find the library.

Order matters. When linking, a library that’s specified earlier will expose symbols to libraries specified later.

Furthermore, when searching for libraries in the above script, it seems that some libraries can’t be found until other ones have already been found. I haven’t figured out why this is the case.

Sometimes, multiple libraries are found in the same path. In that case, only the first library that is searched for needs to specify the path option. Once a library is found in a path, find_library will automatically search that path for subsequent libraries.

However, it’s good to specify the path in all cases as documentation.

The libraries will be linked in the reverse order of the calls to find_library, so search for the libraries in reverse order.

Lastly, we have to call create_makefile at the very end to actually generate the Makefile. The name passed to this function is the same name specified in the SWIG interface file back at the beginning of this post.

And with all these pieces in place, you can run the above script to build your extension.

Because we used dir_config to allow specifying Raylib’s location, we can now pass in the location when running the script. If you installed Raylib in a standard directory structure, with the header file under an include directory and the library under a lib directory, you can use --with-raylib-dir:

ruby extconf.rb --with-raylib-dir=/path/to/raylib

If you have the header file and the library in non-standard locations, like in the same directory, you can specify the location of each separately:

ruby extconf.rb \

--with-raylib-include=/path/to/raylib \

--with-raylib-lib=/path/to/raylib

You don’t even have to specify the location at all, if Raylib is installed in a system-wide directory that gets searched automatically. These locations will depend on your system.

Finally, use the Makefile to build the extension:

make

Now that our extension is built, we can finally use it in a Ruby program! This is the easy part, involving two steps:

Require the newly generated library in your program. In Ruby, require and require_relative can be used to import a shared library (.so on Linux) as if it were a Ruby file (.rb).

Use the methods defined under the Raylib module. These methods correspond one-to-one with the methods provided Raylib itself, making the resulting Ruby code look very similar to C code that uses Raylib.

For example, if the C code would have looked like:

InitWindow(500, 500, "Raylib test");

SetTargetFPS(30);

while (!WindowShouldClose()) {

BeginDrawing();

ClearBackground(RAYWHITE);

DrawCircle(250, 250, 200, MAROON)

EndDrawing();

}

CloseWindow();

Then the Ruby code looks like:

require_relative 'ext/raylib/raylib'

def color(r, g, b, a = 255)

col = Raylib::Color.new

col.r = r

col.g = g

col.b = b

col.a = a

col

end

MAROON = color(190, 33, 55, 255)

RAYWHITE = color(245, 245, 245, 255)

Raylib.InitWindow(500, 500, "Ruby Raylib test")

Raylib.SetTargetFPS(30)

until Raylib.WindowShouldClose

Raylib.BeginDrawing

Raylib.ClearBackground(RAYWHITE)

Raylib.DrawCircle(250, 250, 200, MAROON)

Raylib.EndDrawing

end

The only caveat is that we have to define the colors ourselves, something I’ll talk about in the next section. However, despite the fact the structure mimics that of the C code, we can still access all the power of Ruby to build high-level abstractions.

If you look at the Raylib header, you’ll find a few pre-defined colors, such as:

#if defined(__cplusplus)

#define CLITERAL

#else

#define CLITERAL (Color)

#endif

#define WHITE CLITERAL{ 255, 255, 255, 255 }

#define BLACK CLITERAL{ 0, 0, 0, 255 }

#define BLANK CLITERAL{ 0, 0, 0, 0 }

#define MAGENTA CLITERAL{ 255, 0, 255, 255 }

#define RAYWHITE CLITERAL{ 245, 245, 245, 255 }

These colors are missing from under the Raylib module in the Ruby extension. To understand why, you have to understand some memory management in C. If you’re not comfortable with C, you can safely skip this section. The example code a few paragraphs down will still be useful.

When you use a color like BLACK in C, you’re creating a struct on the stack and passing it by value to wherever you’re using the color. SWIG converts C structures to heap-allocated Ruby classes. In the process, the above defines become meaningless and are not automatically converted to Ruby.

To make matters worse, when a C structure is converted to a Ruby class, SWIG creates a class with no constructor arguments, only setters for each field. This makes creating a new color verbose. One option is to create a color method under the Raylib module, then copy over the colors provided by Raylib (if you so wish):

require_relative 'ext/raylib/raylib'

module Raylib

def self.color(r, g, b, a = 255)

col = Color.new

col.r = r

col.g = g

col.b = b

col.a = a

col

end

# Define all the colors

WHITE = color(255, 255, 255, 255)

BLACK = color( 0, 0, 0, 255)

BLANK = color( 0, 0, 0, 0)

MAGENTA = color(255, 0, 255, 255)

RAYWHITE = color(245, 245, 245, 255)

end

Now you can use these colors as if they came directly from the extension:

Raylib.ClearBackground(Raylib::BLACK)

This is one of the few places where you will need to duplicate some of the declarations inside the Raylib header.

There are still a few problems with our Ruby bindings to Raylib. For example, you won’t be able to use a few library functions out of the box. I’ll go over these problems, and more, in my next post.

Nevertheless, by working through the above steps, I can now write lightweight GUI applications in Ruby. Even without any modifications, just having the ability to combine Raylib with a higher-level language means I can experiment with the UI and behavior of my application more productively than I could using only C.